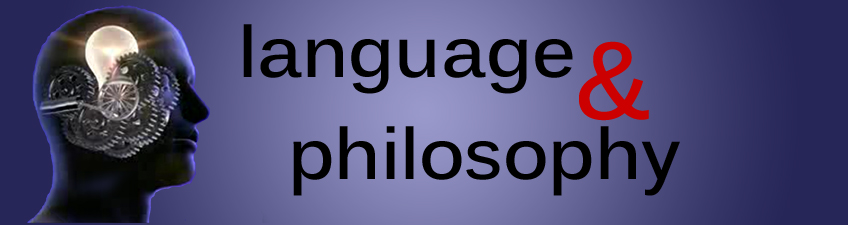

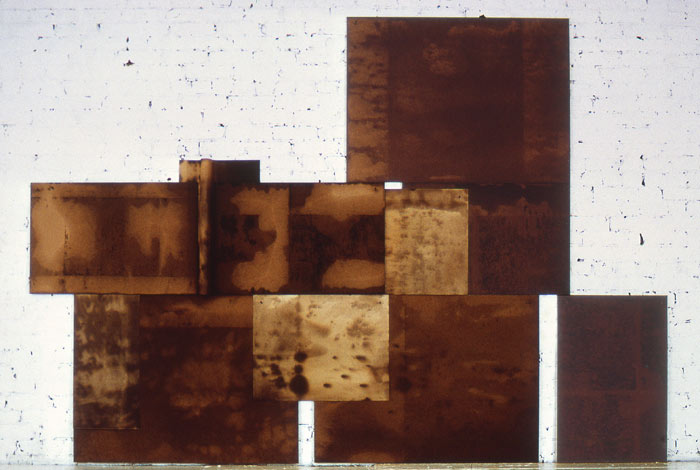

Dorothea Rockburne, Scalar. 72-7/8 x 114-1/2 in. © 2016 Dorothea Rockburne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

If a work of art makes an idea incarnate, what is the nature of the idea and what is the form of the manifestation? One approach to an answer begins with a supposition: The artistic idea consists of an object and a subject. The former contains a characteristic pattern of natural forces. The latter is equivalent to the artist’s transmogrification of the object through the work’s constructive materials.

The dynamics of the artistic idea may be most apparent in a work accessible to the immediate eye. Consider, for example, Portrait of Juan de Pareja by Spanish artist Diego Velázquez. Here the object is the man in the portrait, the characteristic set of natural forces comprising a human being which the creator experienced in an imaginative way. The subject is the developed attitude of the painter toward the object, an internalization of his experience transformed through oils.

The work at the top of this essay, Scalar by Dorothea Rockburne, may seem to lack object and subject. Yet the artist has given much thought to both phenomena. In a lecture at Bowdoin College she identified the artistic object as “a series of experiences which I internalize” and subject as “the act of reaching into the inner existence of extreme human experience.”

What, then, are the object and subject of Scalar? First, some background. Rockburne created the work in 1970 at a time when the prevailing artistic movement was Cubism, defined by the artist as “the abstract representation of an object, as if seen from all angles, and across many moments in time.” Cubism extended a historical interest in the natural object which Rockburne describes in these terms:

Dorothea Rockburne

“For centuries, artists have taken three-dimensional objects—a still life, a human body or bodies, geometric patterns, or a landscape—and, through various methods, transposed and depicted them on two dimensional planes. By following this process, the artists transformed a perceived reality, as presented by an object external to themselves, into a visualized concept.”

By the time of the creation of Scalar, Rockburne felt the need for a fresh view of the foundational object. This feeling found its roots in her studies with Max Dehn at Black Mountain College, where Rockburne learned about set theory and the visualization of the mathematics present in nature. From this time onward, mathematics informed Rockburne’s work and opened the possibility of a new spatial concept.

“Because I was a painter, a question pertaining to art arose,” she recalls. “What is an object? Is thought an object? Is an equation an object?” The artist answered in the affirmative. “Instead of taking a figure, a landscape, or a still life, and making it abstract, as Picasso and the modernists did, I could visualize an abstract mathematical concept.”

The work’s title references that very set of natural forces which is the painting’s object. “Scalar is a mathematical concept derived from a scalar, or diagonal, matrix presented in a visual form,” she stated. “It uses an abstract geometric concept and places it before your eyes so that you can physically observe it.”

While the object of the work was a cognitive concept, it was also to be found in nature, in the form of a wall construction at the ancient Peruvian site of Machu Picchu. “As I viewed photographs of the site, this structure seemed to form a kind of scalar matrix,” the artist recalls. When she visited the location to experience the construction herself, she was spellbound. “The way in which those stones fit oddly together struck me profoundly, as they seem to perform a logic unto themselves. That idiosyncratic pattern spelled out the indication of a matrix I intended to follow.”

The artist’s deep involvement with the mathematical concept made it a productive object for a work of art. “With all its crossover planar incisions, Scalar pulled at me, and excited me. It also seemed very appealing as a thinking paradigm for making art. Because it implies expansion, it seemed a perfect investigative framework through which to explore my thoughts and feelings.”

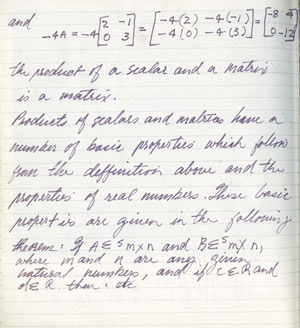

The beginning diary pages for Scalar. © 2016 Dorothea Rockburne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

While championing a new kind of artistic object, Scalar also bucked the contemporary tend toward Conceptual Art, defined by critic Lucy Lippard as “work in which the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary, lightweight, ephemeral, cheap, unpretentious, and/or ‘dematerialized.’” (vii). It was because Rockburne built her work upon a foundation of a cognitive construct that Scalar was included in a 2012 exhibit of Conceptual Art at the Brooklyn Museum. Critic Lippard later told Rockburne that she was “the only artist who had materialized a concept.”

Rockburne’s experience with Scalar provides one answer to the first part of this essay’s opening question. The object of Scalar, the mathematical formula, is a characteristic pattern of forces present in nature. The subject of the work is the transmogrification of the artist’s deep involvement with the object. Together they comprise the incarnated idea. But how does the artist bring about the finished work? Rockburne posed the question this way: “How does the artist reach inwardly to the true emotional subject matter of existence and transform it into a visual language?”

The answer lies in a productive engagement with the transformative principles contained in the work’s constructive materials: “The materials artists choose, with which to make their art, facilitate a translation from the non-verbal to a visual form of subject matter. The tools I choose, the art historical aspects I reference, and my own emotional experiences and thought processes, make themselves available to allow this, often miraculous, journey.”

This cooperative engagement of artist and constructive materials comprises a kind of “thinking through making” which Rockburne feels essential to her creativity: “The only way I can think is with my hands drawing.” This dynamic is not unfamiliar in the field of aesthetics. The critic Maurice Merleau-Ponty noted that Valery claimed an artist “takes his body with him” into the studio and that Cezanne claimed to “think in painting” (123, 139). It is not the mind which paints, concluded Merleau-Ponty, but “it is by lending his body to the world that the artist changes the world into paintings.”

The beginning diary pages for Scalar. © 2016 Dorothea Rockburne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Rockburne extends the concept of “thinking through making” to an important new level in which the materials of construction themselves confess a fecundity as they participate in the transmogrification of idea into material construct. In the case of Scalar, Rockburne described how she constructed a kind of “stacked sandwich” out of the organic materials of chipboard, rag paper, and crude oil. She then left the materials of the sandwich to “cook, that is to say, interact, and influence one another, while partially exchanging identities.”

Rockburne describes the process in these terms:

“The various materials would switch their material positions causing the component parts to either change place or meld into one another. Although my mathematical creative thinking is mysterious, even to me, I compared this process of identity exchange to the somewhat similar steps and processes involved in solving an equation.”

When after some time Rockburne pulled apart the sandwich and nailed its separated parts to the wall, the constructive materials had performed their creative imperative so well that they “practically fell together” into a natural order. The phenomenon recalls Apollinaire’s claim that certain phrases in a poem “seem to have shaped themselves” rather than to have been created (Merleau-Ponty 141).

The incarnation has been accomplished. But what is its nature? This remains the unanswered part of our essay’s opening question. Posit that if the founding object has not been fully transmogrified, the nature of the finished work will be metaphoric, the cognitive construct will be declarative, and the viewer will be disengaged from the primary aesthetic gear. On the contrary, if the artist and constructive materials have subjected the artistic object to fundamental transformation, that is, if the idea of the work has been fully realized, the finished work will neither imitate nor shadow the object of origination but will cast its ineffable recollection upon the mind of the viewer.

The nature of the finished work will hence be anamorphic. All such phenomena have in common an apparent deformation, which remains in a state of distortion whatever the angle of the viewer, but which pops into regular proportion, albeit resisting logical resolution, when observed from a suitable position. In the case of a work of art that position is equivalent to a dedicated viewer who successfully engages with the native principles of the attending constructive materials. The successful work is characterized by a state of repeatable and varied co-creations by the skilled viewer.

In contrast with a metaphoric work, what is carried away from an anamorphic one is neither a propositional conclusion reached through ratiocination, nor an emotion arising from feeling, but a sense of value determined by an experience of completion of an idiosyncratic cognitive construct. The end result for the viewer is not enlightened insight but a refined consciousness arising from a heightened sensitivity to natural forces.

If reality is ineffable and language is inadequate, the process outlined in this essay is little more than a sketch. The artist’s creation of an anamorphic construct is less of a straightforward dealing with mathematical formulas and more of an undefined, unconscious invigoration of constructive materials. Rockburne describes the process in these terms:

“There’s an emphasis put on mathematics in my work because it’s easier to talk about than what is really going on, which is visual. It’s a visual language. It’s a complex language. It’s an art language. It’s a mystic language. And all those things are hard to convey.”

Essay by Walter Idlewild.

Images courtesy Dorothea Rockburne.

Works cited

Lippard, Lucy. Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. U of California P, 1997.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. “Eye and Mind.” The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader. Northwestern U P. 1993.

Rockburne, Dorothea. “Materializing Mathematical Concepts into Visual Form.” Lecture delivered at Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine. April, 2015. Transcript courtesy the artist.

Additional statements by the artist from an interview with Walter Idlewild in September 2016.

Posted December 4, 2016