Sharon Stepman, Next Day on Times Square, 2006. Digital image.

As he walks through a looking glass in the film that bears his name, Orpheus finds himself surrounded by objects that recall but do not replicate the world he has left behind. These strange but oddly familiar abstractions seem to reveal truths that can neither be understood by reason nor expressed by language. In their wake is a transformed reality energized by hidden principles whose expression would defy the agency of forms untethered to the natural world.

The Orphean mirror will be a familiar device to any creative individual who lines a canvas with abstractions. It is through the distortion of familiar objects that the artist allows hidden but vital principles to appear. The process is a formal paradox: The truth of nature can only be given through falsehood. And like Orpheus in his cinematic underworld, the viewer of these works leaves behind the certainties of nature for a more comprehensive understanding of the subjects rendered. The result is an entry into a higher reality for both creator and viewer.

Sharon Stepman

It is this very transformative engagement which explains why Sharon Stepman refers to her works not as photographs but as “images that do not exist in the real, which rise to another level and become metaphors for themselves.” A case in point is the artist’s latest initiative—images of homeless people that seem more the revelations of a prophet than the journal of a disengaged observer. Here humanity is presented in its full measure, bodily surfaces obscured by forces within and without. In her images we see the homeless people in a more comprehensive way, thanks to the creative distortions introduced by the artist and her constructive materials.

Stepman became interested in the plight of the homeless a decade ago when she began work on a book project titled New York Transfer, to be published in France by Biro Editeur with text by Jake Lamar. Fascinated by Lamar’s text, the photographer began to see New York in a new light. Prior to the COVID-19 lockdown, New York City had 60,000 recorded homeless people—a number that has doubtless increased. “This pandemic will bring additional people out into the streets,” says Stepman. “We must take responsibility for what our government has created.”

The result was a series of images that would communicate what Stepman saw as a crisis. “I wanted to present the inhuman side of our city,” she says, “the degradation of the people in the streets and the acceptance of a strange contradiction between riches and desolation.” She might have documented the social issue with realistic photographs, easily recognizable records of the abysmal conditions in which the homeless people dwell. For Stepman, though, the goal was not so much a social documentary as a revelatory expression of easily overlooked forces that are part and parcel of the homeless experience.

Sharon Stepman, With Doll and Flowers, 2002. Digital image.

Form, then, was to follow function. Stepman knew she could only reach her ambitious goal through the use of abstraction. If the technique is often viewed as a stretch for photography, it has long been a revered tradition in another medium to which Stepman had applied her skills years earlier. The art of oils and canvas has a long history of attempts to provide a fuller view of the real by rendering the unseen aura of its subjects. It is to the point that even artists known for their abstractions have insisted on a realistic basis for their convolutions. Picasso claimed his works “have always been in the essence of reality” and Jasper Johns said his works were “my idea of what is real.”

Stepman informed her photographic images with the lessons drawn from her earlier work on painting. But what abstractions, exactly, would do the job? The answer relies on an arcane recipe of experience, intuition and observation. At a more practical level, many productive abstractions arise from the exploitation of the limitations inherent in the constructive materials on the artist’s chosen palette. It is for this very reason that Stepman has long employed black and white film—an excellent example of a medium with innate restrictions that immediately divorce the work from nature while providing a fertile ground for creative exploitation. “Black and white to me is a very strong medium,” says Stepman. “And of course, it’s something that already starts to pull away from reality.”

Stepman’s approach recalls a similar attitude by photographer W. Eugene Smith. Charged with creating a portrait of Pittsburgh and its people for Life magazine in the 1950s, Smith deliberately avoided the term “documentary” for his work, protesting that the word “can do mischief by giving people the wrong idea that the outside or surface of things is enough for a picture.” Rather than create a record of city landmarks, Smith desired to capture “the character essence of Pittsburgh” so viewers would see “the city as a living entity.” Again utilizing a black and white medium, Smith leveraged what he called “the compromises and deliberate shortcomings built into film and paper” by methods such as, for example, darkening a shadow by using ferrocyanide.

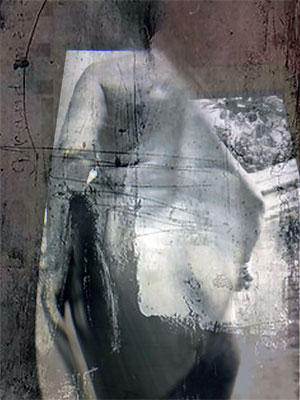

Sharon Stepman, Street Woman 10, 2019. Digital image.

While exploiting greyscale limitations by accenting formal components such as chiaroscuro and contrast, Stepman has also deepened her creative canvas in subtler ways that obviate the common tendency of surface colors to overwhelm a subject’s delicate principles. For example, she has leveraged the multi-color nature of black and white images when processed by modern ink jet printers.

If the above reasons explain why black and white film had long been a useful medium for Stepman, it is ironic that the artist abandoned the medium for her homeless series. The reasons recall the aforementioned inexplicable recipe that determines the selection of abstractions and their media. It can only be said that the topic at hand demanded another treatment. “Most of the time with the homeless, I have worked with the color that was there,” she says. “And I think maybe it is because this particular series is more into surface reality. These people on the streets are real.”

As it happens, other restrictions presented themselves as possibilities for exploitation. One was an inexpensive camera called the Holga which had participated in the artist’s creative process by offering limitations just as fertile as those inherent in black and white film. “The Holga has a cheap plastic base and lens,” Stepman says. “I like the distortions they make.” One such distortion is the coarseness of the transformed image—The lens lacks the command of fine details characteristic of advanced cameras. Another is accidental vignetting, or gradation of brightness and saturation from the edge of an image to its center. Still others are blurring and occasional leaks of light through cracks in the cheaply constructed box.

Another useful restriction arises from the device’s offset viewfinder which offers the photographer a vision that differs from the one being captured. “With a single lens reflex camera you can see the image of what you are taking,” says Stepman. “The Holga, on the other hand, has a mind of its own.” It is that independent cognition which introduces the concept of serendipity—a principle Stepman finds especially productive. “The idea of chance is fascinating for me,” she says. “There are some artists who want to be in control, I’m sure, but that is not something that interests me. I prefer to be surprised at what the Holga decides it wants.”

Sharon Stepman, Bus Ride on 5th, 2021. Digital image.

Productive it may be, but chance alone will not produce the required artistic result. Stepman emphasizes her work is a collaborative effort. “I am still in control up to a certain point,” she says. “I am still looking at the subject, the person, what’s in front of me. I don’t think either the camera or I alone makes the image.”

While the Holga has been a faithful artistic companion for Stepman, the artist again found the need to abandon the tool for her homeless series. Limitations, it seems, can restrict as well as expand the aesthetic effort. In the case of the Holga, the nonexistent aperture and speed control created an unsolvable dilemma (even with high-speed film) in the limited light conditions of a subway platform or other location where the homeless often live. Another practical problem was the camera’s loud clicking sound, a consequence of cheap construction which proved distracting to the photographed subjects. And then there was the challenge of finding a convenient place to develop the black and white film—one which became harder as time passed.

Stepman sidestepped all these problems by using a digital camera. The risk, of course, was the potential of reversion to the unidimensional images such equipment allows. The artist resolves this issue by deliberately reworking the digital imprint. “I try to uncontrol the image, to turn it back into something more like what the Holga might have given me,” she says. And there was another restrictive opportunity: Color filtered through photographic media tends to differ from that of nature, and the artist can manipulate that distortion for desired effects. “Sometimes I take the color out of the original image, which computers make easy to do, and add layers that make the image become something else.”

If this creative editing reintroduces the very restrictions modern photographic equipment was designed to eliminate, it was not entirely new to digital production. “Even with the Holga, I would always screen the images, scanning them first and then creating layers,” says Stepman. She continues to experiment with new ways of manipulating her work, sometimes bleaching parts of the image and other times scanning the objects directly or even rescanning them onto archival paper, a medium that further divorces the finished product from surface reality. “I create the image after I take the photograph,” says Stepman. “It’s not satisfying to me to leave it the way it is when it comes from the camera.”

Sharon Stepman, Venus, 2021. Digital image.

Not everyone is enamored of the root process in play. Some people believe image editing is dissimulation: A photographer, they say, should present reality as captured by the camera’s snap. As recently as 2009 the New York Times found it necessary to remove a photo essay with images discovered to be “digitally altered, apparently for aesthetic reasons,” because they “did not wholly reflect the reality they purported to show.”

In the mid-twentieth century W. Eugene Smith defended his work against charges that his darkroom machinations amounted to “cheating” and “manipulating the truth.” Today, Stepman has a ready retort for anyone– such as a recent collector in Rome– who questions the authenticity of her own manipulated photographs. “The truth is that there isn’t any photograph, no matter who does it, that is not burned and dodged in the dark room,” she says. “Do you call that manipulation? I do. And if somebody doesn’t think that all images are manipulated, well, they’re mistaken as far as I’m concerned.”

Stepman has created some 300 images of homeless people and plans to continue her work as long as she feels it can raise the consciousness of viewers to a worsening condition. Like Orpheus entering the underworld, though, some viewers may be confused by the surface distortions of the Stepman images. That confusion can best be dispelled by an understanding that the purpose of these works is not so much the production of a definitive statement about homelessness as an increase in public sensitivity to the complexity of the natural forces surrounding the experience of people who live on the street. Each viewer will engage with this heightened consciousness in an idiosyncratic way. Perhaps the last word had best be given to director Jean Cocteau, who, in his spoken preface to Orpheus, invites viewers to “interpret the film as you will.”

Sharon Stepman’s images have been featured in exhibits at Giardino di Boboli, Florence, and The People’s Forum, New York City. She provided the images for New York Transfer, published by Biro Éditeur, Paris.

Essay by Walter Idlewild.

Images courtesy Sharon Stepman.

Posted November 13, 2021.

Unattributed statements by Sharon Stepman were recorded during interviews with Walter Idlewild in October 2021.