Picture a charming restaurant in the Paris of 1965 where a young writer named Robert J. Seidman is waxing enthusiastic about a novel he’s just read. “Isn’t Ulysses great?” he enthuses to his companion, a considerably older gentleman of Irish extraction. “I think it may be the best novel I’ve ever read.”

Picture a charming restaurant in the Paris of 1965 where a young writer named Robert J. Seidman is waxing enthusiastic about a novel he’s just read. “Isn’t Ulysses great?” he enthuses to his companion, a considerably older gentleman of Irish extraction. “I think it may be the best novel I’ve ever read.”

Alas, the individual to whom this question was put happened to be in the possession of a mouthful of Guinness which at once entered a state of aerated propulsion across the table. Seidman recalls the response that ensued: “He spun toward me and said, ‘I hate that—' he didn’t say ‘God damn book.' It was a little stronger.”

“Why?” Seidman responded. “It’s the most inventive and ambitious novel I’ve ever read.”

“No, I don’t hate it because of that,” was the retort. “I hate it because it’s so real. I feel like I’m back in Dublin, and that’s the one place I always wanted to get out of.’”

In the more than half century that has passed since that Parisian conversation, Seidman has devoted much of his life to the close reading of Ulysses. His years of study have confirmed the moral of that Parisian encounter: James Joyce’s novel provides just as dependable a picture of early twentieth century Dublin as it does of the human heart. “People who believe Ulysses is not realistic,” he says, “are not correct.”

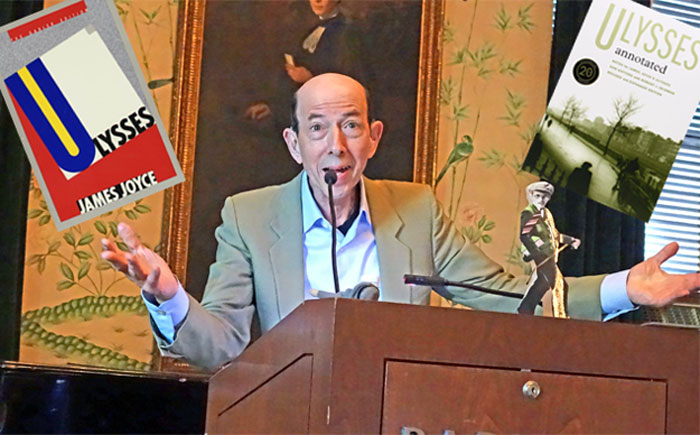

Seidman is in an excellent position to know. He and Don Gifford are, after all, authors of the most detailed encyclopedia ever published of Joycean esoterica: Ulysses Annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses (University of California Press, 1988). Earlier this year at Barnard College, in a presentation entitled “Inexhaustible Ulysses,” Seidman treated an enthusiastic audience of some 50 people to his reflections about a novel that many people feel is the greatest ever written.

“Ulysses is a dauntingly ambitious book,” he opined to the crowd. “An attempt to write a modern epic that captures the simultaneity, confusion and layered nature of what it’s like to live in a small, yet highly complex, early 20th century urban setting. The novel is hilarious, sexy, moving, intentionally encyclopedic, and perversely erudite. At its best, which is most of the time, Ulysses suggests how rich and interesting life can be; how varied and various human possibilities are.”

And yet. Who has the time? Ulysses is notoriously challenging for any but the most dedicated reader. And in the age of Twitter is there room for the elaborate musings of an author unschooled in the rhetorical power of the 140-character proposition? Even today’s longer winded novelists have abandoned the formal experimentation of the early twentieth century in favor of the greater accessibility—to say nothing of the greater sales potential—of plain talk.

“Disgruntled critics have argued that Ulysses is forbiddingly modernist, demands too much effort, and is willfully difficult,” acknowledged Seidman. And it’s true, he added, that “The novel demands a good deal of effort to dig out several of its tastiest morsels.”

But therein lies its value. “Why is difficulty bad?” posed Seidman. “All art demands some knowledge or application to appreciate it. The more informed insight you can bring to a fine work, the more you fathom its context and its references, the richer it becomes. Since art isn’t fast food, it needn’t be instantly consumed.”

Patient souls who attack the Joycean meal are treated to plenty of nourishing details. Indeed, many attribute the novel’s difficulty to Joyce’s “perverse desire to lard the text with everything he ever knew,” as Seidman put it. Even so, anyone feeling adrift on a sea of allusions can restore their bearings by utilizing the aforementioned encyclopedia. Far more confusing, in Seidman’s estimation, was Joyce’s decision to eliminate the narrator and that ghostly presence’s helpful habit of shepherding the reader through the events of the narrative. “Joyce steadfastly refuses to comment on his story most of the time,” said Seidman. “There is almost no intervention, no editorializing, and no setting of the record straight.” What’s left on the page is the “ideal artistic detachment” reminiscent of Joyce’s archetypical artist from Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, famously trimming his fingernails. The result isn’t difficult to foresee, noted Seidman: “Since the reader isn’t told how to respond to events, characters or crises, it’s easy to get lost.”

Patient souls who attack the Joycean meal are treated to plenty of nourishing details. Indeed, many attribute the novel’s difficulty to Joyce’s “perverse desire to lard the text with everything he ever knew,” as Seidman put it. Even so, anyone feeling adrift on a sea of allusions can restore their bearings by utilizing the aforementioned encyclopedia. Far more confusing, in Seidman’s estimation, was Joyce’s decision to eliminate the narrator and that ghostly presence’s helpful habit of shepherding the reader through the events of the narrative. “Joyce steadfastly refuses to comment on his story most of the time,” said Seidman. “There is almost no intervention, no editorializing, and no setting of the record straight.” What’s left on the page is the “ideal artistic detachment” reminiscent of Joyce’s archetypical artist from Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, famously trimming his fingernails. The result isn’t difficult to foresee, noted Seidman: “Since the reader isn’t told how to respond to events, characters or crises, it’s easy to get lost.”

Joyce wasn’t the only writer to abandon a tour guide. Stripping art to its core was part of the larger modernist movement. “Everybody– Pound, Eliot, Stevens– plunged you into the experience,” said Seidman. “They didn’t tell you what was going on. They didn’t erect billboards that pointed the reader’s way or editorialized about what the author believed was significant.” This was partly a reaction to the intrusive narrator of the 18th and 19th centuries. “Think about Dickens, for example, and as wonderful as he is, how often he tells us where we’re going,” said Seidman. “I think that modernists said, ‘We’re not going to give you the guideposts that you had.’ It’s as simple as that.” Making art more difficult, more esoteric, was part of a larger issue in the air at the time, an attitude of “screw the bourgeoisie” and that class’s love of accessible art. In the place of middle class values artists offered a kind of mystery cult conflating spirituality and high culture. “This was a new and secular religion,” said Seidman. “Artists in many fields were saying ‘I’m not going to explain this stuff for you. It’s like jazz: either you dig it or you don’t. If you don’t get it, get lost, get away from here. We don’t want you as a reader or auditor.”

There was another, formal, reason for the forced retirement of the narrator: For a writer with a desire to replicate the honeycomb of connections among a city’s disparate detail of character and event, the narrator can be in the way, get a bit underfoot. Seidman: “Joyce needed speed, and the ability to talk about the city in terms of simultaneity, with overlays of sound and movement.” That led to his use of multiple styles to reflect the multiple worlds that existed on one imagined mid-June day in 1904. Seidman expressed the rigorous energizing excitement of experiencing such a style in these terms:

“As readers, we are danced and spun and whirled, and sometimes shimmied and schlepped through a linguistic, phantasmagoria in which a master wordsmith regales us with a welter of metaphors, a plethora of puns, effervescent and seemingly inexhaustible wordplay.”

“The verbal pyrotechnics never cease, as the reader is given gouts of slang, a thieves’ cant, snippets from a dozen languages, a capsulated history of English prose, and in the penultimate chapter, is plunged into the rigors of scientific inquiry in the form of an extended, mind-stretching question and answer exchange, based on and parodying the Roman Catholic catechism.”

Energizing it may be, but this riotous rainbow of style allows for no slack in the acolyte’s devotion. In the negotiation of form and the making of meaning Ulysses demands equal workbench time for audience and author. Is it all worth it? Seidman says yes. Ulysses has attracted loyal followers in its near-hundred year history for its clear evocation of the human condition and its aura of life’s humor and pathos. “When a reader does penetrate to the essence of the experience, Joyce’s master work offers enduring, life-enhancing pleasures,” said Seidman. “It’s a bit like eating Chesapeake Bay hard shell crabs, or successfully extricating the body meat of a lobster. It’s an exquisite harvest for those willing to do the digging.”

—

“Inexhaustible Ulysses,” presented May 11, 2015, was sponsored by The Association of Literary Scholars, Critics and Writers Robert J. Seidman was introduced by poet Phillis Levin; arrangements were facilitated by Saskia Hamilton.

Story and photographs by Walter Idlewild

Posted June 12, 2015