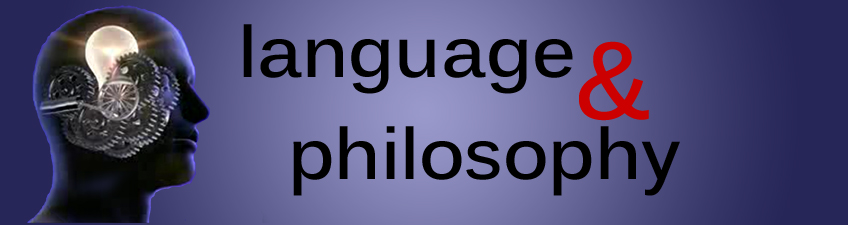

Kathleen Gilje, Etta Dunham, 25 x 20.25 in; Mrs. Fisk Warren, 25 x 20 in; Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, 25 x 19.25 in. From a series of 48 paintings after John Singer Sargent, 2007. Oil on linen.

What disturbs conventional forms of art? What mechanisms shatter comfortable patterns of constructive materials, allowing new structures to rise to prominence? As one approach to an answer, consider the formal innovations of Kathleen Gilje, an artist who has established a reputation for technical proficiency rivalling the Renaissance masters.

The skill was hard earned. Gilje began honing her talent as a young woman working weekends at a high-end New York City furniture restoration shop. “I’d brought a portfolio with me when I applied for work, so they started to give me the artistic things to do,” she says. “If a piece of furniture came in with a Japanese or Chinese painting, I would be asked to repair the damage.” Gilje learned to love such work, rising to the challenge of an occasional free-standing painting that would arrive at the shop. Then, in the mid-Sixties, there came an opportunity to travel to Italy. Captivated by the land and unwilling to leave, she applied for an apprentice position at the studio of Antonio de Mata, the renowned restorer of antique paintings. Gilje nervily told her prospective employer that she had worked as a conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Of course, he knew that was a lie,” she says. “In any case I got the job and started in the studio by sweeping floors and doing all the old-fashioned apprentice things.”

Kathleen Gilje

Gilje was put to work on minor paintings, then moved on to more valuable treasures as her skills increased. The pay was modest: $50 a week for working five days and Saturday morning. More important than the money was the career boost: “I learned about conservation from a master,” she says. “De Mata was very well known, so there were some amazing paintings coming into his studio.” At some point Raffaello Causa, director of the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, asked De Mata to work on some valuable museum paintings. Gilje joined a troop of workers shuttling between Rome and Naples, enjoying what many would consider a fairy-tale existence. In the former city she maintained an apartment behind St Peters, and in the latter she resided inside the Museo di Capodimonte itself. “They pulled some old furniture they had in the basement—some things that had once belonged to kings—and put it in our rooms,” she says of her makeshift lodgings.

It was during these labors that Gilje came to appreciate many of the old Italian masters from the 1500s and 1600s. She was particularly fond of the works of Jusepe de Ribera, Massimo Stanzione, Bernardo Cavallino, and especially Caravaggio. Restoring their works taught Gilje about their lives and about their use of paint and brush. “When you restore a painting you are like a detective,” she says. “You have to figure out what’s going wrong, then how to return the work to health without doing any harm or diminishing the original.”

After six years in Italy Gilje experienced an event that would affect her career in practical and thematic terms. While working as a restorer she had been developing her own art, and now she felt it was time to advance her career. It didn’t go well. “A Milano gallery offered to show my work,” she recalls. “But they canceled when they found out I was a woman. They told the person who had helped me get the show, ‘She’s just going to get married and have kids, and we don’t want to invest in somebody like that.’”

Kathleen Gilje, Donna Velata, Restored, 1995. Oil on canvas, 33.5 x 25.25 in.

Gilje began to question the wisdom of remaining in Italy, not only because of the response to her sex but also because she had come to recognize certain limitations of the society. “I was young, but I was very observant,” she says. “I thought to myself, everything in Italy is based on family. Power is based on family. And when you have no family there, you’re powerless. So, I decided if I wanted to be an artist I’d have a better chance if I came back to the United States.” She returned to New York in 1972.

Gilje’s experiences with the Milano gallery had impressed her with an important truth: Societal norms impose restrictive pre-conditions upon artistic achievement and recognition. This truism was reinforced by the writings of Linda Nochlin, an author who would have an important influence on Gilje. “Nochlin’s 1971 essay, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’, shocked the art world and made women sit up and take notice,” says Gilje. “Her writings became a real inspiration for me, a road into the freedom of saying I can see things and I want to share what I see.”

If cultural structures and societal norms influence the art produced by women and their professional status—a postulate advanced by Nochlin and experienced first-hand by Gilje—it was also true that the art of the Old Masters contained signs that operated as hidden codes for those very norms, as testaments to an invisible but powerful male prerogative. Gilje responded to this reality by moving her work in a new direction. She would capitalize on her technical skills to create works that would on the surface resemble the Old Masters but would also distill into visible images the previously hidden principle of male power that had energized them. Just as Gilje’s previous restorations had brought to health old works by repairing shattered paint, what she called “contemporary restorations” would cure them at a deeper level by forcing to the surface previously repressed truths.

While the visibility of male power and the restoration of women’s humanity is not the sole theme of Gilje’s work, it predominates in many of her best works. Examples include Susanna and the Elders, Restored (after Artemisia Gentileschi); and Het Pelsken, Restored (after Rubens). And in a series titled 48 Portraits: Sargent’s Women, Restored, Gilje returns Sargent’s women to their true selves by removing clothing which had defined them by their positions in society as wives of famous men. All of these works communicate ideas that have for centuries been enduring threads in the human fabric. “The method of showing an idea may be contemporary,” she once said in an interview with Francis M. Naumann. “But the idea itself can be traced back to the beginning of time.” This is illustrated in her restoration of Raphael’s La Donna Velata, in which the titular image has been given a bruised eye representing the timeless prevalence of abuse. “Today we may hear about abuse and talk about it, and try to confront it, but it’s not a new issue,” says Gilje.

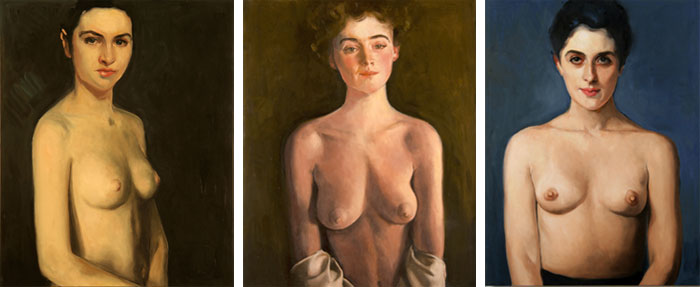

Kathleen Gilje, Woman with a Parrot, Restored (after Courbet), 2001. Oil on canvas, 51 in x 77 in.

Gilje’s paintings visualize what Nochlin had identified as “the very presence of an intruding subject” which was “the hidden ‘he’ as the subject of all scholarly predicates.” A dramatic example of just such intrusion is Gilje’s Woman With a Parrot, Restored (after Courbet), a work in which Gilje has added a sexualized image of the painter Courbet standing at the foot of the model’s bed. “This restoration was based upon Michael Fried’s writings of the painting and the idea of the male gaze,” says Gilje. “To play on that concept I have the artist jump into the work, so the male gaze is actually present in the painting itself.” Courbet gazes upon a woman who does not speak, acknowledge his presence, or represent a threat. Neither does the woman engage in a sexual act: Her sole mission is to allow the man the pleasure of the gaze and the ability to return to the woman time after time with no fear of commitment and no need to subject his life to the complication of communication.

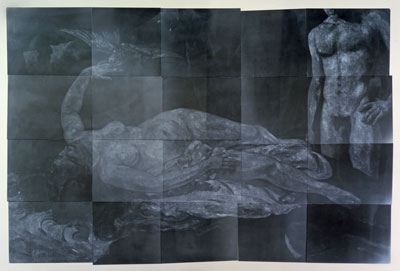

Kathleen Gilje, Woman with a Parrot, Restored (after Courbet), 2001. X-ray, 50 x 75.5 in.

A formal twist here is the use of lead paint to realize a thematic vision: Courbet’s gaze can be seen by the modern viewer only through the utilization of X-ray technology that is practically a stand-in for the “new eyes” that Nochlin said were necessary to view Gilje’s restored works with “virgin vision, as though for the first time.” In a bow to the demands of exhibition, museums have shown Gilje’s hidden image on sheets of X-ray film mounted beside the more traditional oil painting.

Gilje’s explicit restorations of male intruders in Parrot and many other works remind one of The House of the Sleeping Beauties, a novel by Yasunari Kawabata in which male clients enter a commercial house’s secret rooms where they spend the night with companions doped by powerful medicines into unnatural stupors. The arrival of the novel’s protagonist and house patron, an old man named Eguchi, to the room of a sleeping woman is eerily similar to the arrival of Courbet in Gilje’s painting. And Kawabata’s titular entities are strikingly similar to the women pictured in Old Master paintings. Because they lack consciousness they are conveniently nonresponsive to the male intruder and unable to engage in any dialog which may break the aesthetic spell. As remote as they are close, they may be enjoyed without inconvenient commitment. They are also anonymous, lacking history, personality and humanity. All of these women are invaded by Kawabaki, his proxy Eguchi, and the reader, as much as the painting’s woman with her parrot is invaded by the male gaze of Courbet. In short, the women are objectified. It was impossible, thinks Eguchi of one woman, that she should “have had a child, that her breasts should be swollen, that milk should be oozing from the nipples.” When one woman dies the house madam tells Eguchi not to worry about the loss, for “there is the other girl” to enjoy.

In an acknowledgment of the sleeping beauties’ resemblance to works of art, Kawabata says the women have been “put to sleep for the purpose” of being “looked at.” And just as art is sometimes referred to as a living thing, so are the young women “alive while asleep.” The clients, mostly impotent, may caress the beauties with their eyes as a viewer might a painting, but in common with the latter may not engage in sexual acts, or indeed in any acts of “bad taste” with what are described as virgin prostitutes.

Kathleen Gilje, Het Pelskin, Restored (after Reubens), 2001. Oil on wood, 69.75 x 33.5 in.

As agents of revelation, the male intruders of Gilje and Kawabata make an appearance as well in Jacques Rivette’s La Belle Noiseuse, a film which introduces another painter of nudes—the fictional Frenhofer—into a modern restoration, a reverse ekphrasis, of yet one more revered artifact of Old Master craftsmanship—Balzac’s novelette The Unknown Masterpiece. In both film and novel, a woman feels her humanity erased by the act of modeling, and as a result ceases to love the man who committed her to the work. The film maker, though, shifts focus somewhat from Balzac’s painterly process to the psychology of the woman, empowering her as a self-assertive agent who recognizes the damage done, in the process disrupting the narrative of Balzac’s novel just as surely as Gilje disrupts that of the traditional painting.

Painter. Novelist. Film maker. All are engaged in a revelation of the secret forces which underlie society and art. And all seek solutions to the aesthetic puzzle identified by philosopher Roland Barthes: How can an artist avoid the endorsement of a false clarity, brought about by an investment in that complex of coded signs embedded in every artistic medium? For Barthes the solution lay largely in what he called “writing degree zero,” a deliberately poetic style resulting from the conscious elimination of the deleterious codes embedded in language. Practitioners of the plastic arts have responded to the Barthesian challenge with works of pure abstraction in which the subject is exclusively an effect of materials. At first this would seem to be the sole solution, for, after all, an artist can hardly present a competing set of coded signs without becoming a propagandist. “Art which states a position,” insisted Nochlin, “is no longer a work of art.”

Confronted with a tyranny of coded signs, then, the creative individual would seem to be trapped in a work’s enveloping form and confined to the production of non-representational works which were, Barthes believed, cloaked in a desperate privacy. In an intriguing formal twist, however, Gilje offers an alternative solution arising from the realization that Old Master paintings are not so much lies as half-truths: While truly signifying male prerogative they fail to disclose the damage done to the female, as well as her response and resistance. Why not complete the truths of the paintings, then, by highlighting their unspoken assumptions? Instead of eliminating the work’s coded signs or balancing them with competitors, Gilje adds complementary ones that jolt viewers into a higher state of consciousness. This paradoxical mechanism restores the revered works by possessing their formal structures, and destroys their coded objects by borrowing them. The result is a dramatic realization of Barthes’ wry maxim: “Revolution must of necessity borrow, from what it wants to destroy, the very image of what it wants to possess.”

Gilje’s contemporary restorations provide an answer to this essay’s opening question: Artists disrupt old forms in response to a higher state of sensitivity to natural forces. In disturbing the surface of revered paintings Gilje does not so much offer a new interpretation informed by modern sensibilities as restore the works to their full meaning. For the viewer, the result is not so much a communication of moral propositions as an elevation of that attunement to subtle principles which generates meaning in a successful work of art. So do Gilje’s restorations, in Nochlin’s assessment, make everyone think and see differently. Today’s viewer must decide whether to interact with the restored paintings using X-ray eyes that see moments of truth rather than proofs of a code or, like old Eguchi, to “sleep a deathlike sleep beside a girl put into a sleep like death.”

Post script: Kathleen Gilje is currently working on a series of 12 oil portraits of teenage girls. The images are combined with text taken from interviews with contemporary High School girls on their lives, concerns and dreams. The portraits’ heads are taken from William Bouguereau, as well as from Victorian photographs of young girls of color. The bodies are based on living models.

Essay by Walter Idlewild.

Images courtesy Kathleen Gilje.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Writing Degree Zero (1953). Hill and Wang, 2012.

Nochlin, Linda. Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader. Thames and Hudson, 2015.

Rivette, Jacques. La Belle Noiseuse (1990). New Yorker Films, 2004.

Unattributed statements by Kathleen Gilje were recorded during interviews with Walter Idlewild in June and July of 2017.

Posted July 11, 2017